The Magic of Ethnography and Observation in Medical Design

- Laura Karik

- Dec 16, 2024

- 4 min read

Ever wondered how those nifty medical devices come to be? Well, a lot of it boils down to good old-fashioned observing and understanding people—something that ethnography and observation do pretty well. Imagine being a "fly on the wall," just hanging out and watching how folks use medical tools and interact in their workspaces. This way, designers can really get a feel for what users need and why they do what they do.

Ethnography is basically this method where you study people and their behaviors up close. In design, it means watching and learning from the people who actually use the products you're creating. It’s like living in their world for a bit to see what makes them tick, what frustrates them, and what makes their day.

One cool way to do this is by being a "fly on the wall." You just sit back and watch how people interact with devices, tools, and each other without interfering. This method is great because it captures genuine behaviors and reactions—like a candid camera of sorts, but for research!

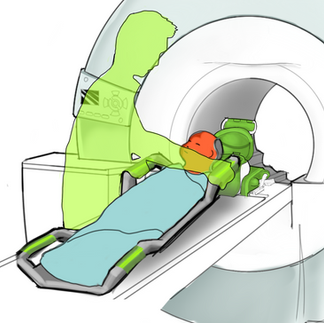

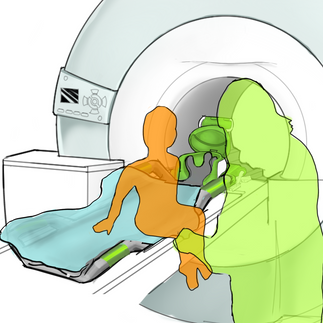

The XLR (now ceresensa) developed a high performance head coil technology that promised faster imaging time, making it ideal for Pediatric imaging. The Kangaroo Group team, was contracted by them to develop the design and prototype a solution. To get it right, the design team spent eight hours shadowing MRI technicians at Boston Children's Hospital.

During this time, the team noticed a big issue: kids were super anxious about the MRI machine. This anxiety not only scared the kids but also messed up the scans because they couldn’t stay still. This was a major roadblock, slowing down the whole imaging process.

With these insights, the team came up with two awesome solutions. First, they redesigned the head coil to look more like a fun, space-themed helmet. The idea was to make it less scary and more like an adventure for the kids. Imagine a little astronaut ready to explore space!

For kids who needed sedation, the team developed a mechanism to help position and hold the kids still, which could easily fit with the head coil. This way, they wouldn't wake up during setup, making the process smoother and quicker.

Another fantastic example is the development of a machine to preserve lungs following a transplant by XOR Labs (now Traferox Technologies). The Kangaroo team worked closely with the surgical team, spending extensive time observing existing procedures to identify pain points and opportunities for strengthening the IP of the Ex-Vivo Lung Perfusion (EVLP) technology.

By being "flies on the wall," the designers could see firsthand the challenges faced during lung preservation. They noted the intricate steps involved and the stress points where things often went wrong. This deep understanding helped them pinpoint specific areas where new intellectual property could be developed to streamline the process.

From a designer's view, observing people isn't just about figuring out what they need; it's about understanding why they need it. Like in our examples, knowing that the kids' fear was partly due to the intimidating look of the MRI machine and the clinical environment itself led to broader design considerations. Similarly, observing a complex procedure such as lung preservation procedures led to identifying more efficient and user-friendly solutions to save time and success rate.

This method isn’t just limited to medical devices; it can be applied to a wide range of products and services. Think about it like this: Imagine a beautifully landscaped park with neatly designed paths. These paths represent the intended user journey—a guided, planned experience. But if you look closer, you'll often see worn-out trails cutting across the grass. These "desire paths" show the routes that people actually take, revealing the most efficient or preferred ways of moving through the space. It's a powerful visual analogy for how real-world observation can inform better design.

By applying the "fly on the wall" method, designers can identify these "desire paths" in various contexts:

Consumer Electronics: Observing how people use their gadgets at home or on the go can uncover pain points and opportunities for new features. For instance, designers might notice that users consistently place their phones in certain spots or hold them at specific angles, leading to improvements in ergonomics or accessibility features.

Retail Spaces: Watching customers navigate a store can reveal natural shopping patterns, helping to optimize store layouts, product placements, and signage for a better shopping experience.

Software and Apps: Monitoring how users interact with digital interfaces can highlight areas where they struggle or find intuitive paths that weren't initially considered. This can guide UI/UX improvements to make software more user-friendly and efficient.

Public Services: Observing how people use public transportation, healthcare facilities, or other services can inform more user-centric policies and designs that better serve the community.

Thes are just a few examples of how powerful ethnography and observation can be during product definition. By using this method, designers can create products that are not only practical but also resonate emotionally with users. It’s about making a meaningful difference in their lives.

Ethnography and observation are like the secret sauce in design. Being a "fly on the wall" gives designers valuable insights into how people use and feel about their products. This approach helps create solutions that truly fit users’ needs and improve their overall experience.

So, next time you see a well-designed product, remember that a lot of thoughtful observation and understanding went into making it just right.

Comments